Brian James Stone, Indiana State University

Situating Irish Rhetoric

The medieval Irish rhetorical tradition begins in the fifth century CE with arrival of the Romano-Briton bishop, Patricius, better known to us today as St Patrick. With the arrival of the Church in the fifth century came literacy, and the following centuries saw a flowering of Latinate and vernacular literature and learning, including grammatical handbooks (both Latin and vernacular), poetry, liturgical texts, hagiography, hymns, poetry, saga, dindshenchas (“lore of place-names”), triads, scriptural and grammatical commentaries, and law-texts. The Irish were known by their British and Continental colleagues for serc léigind (“a love of learning”), and in the earliest centuries the Irish monastic schools had a stellar, international reputation.

Verbal art and oratory were central to early Irish society, with native practices of satire, praise, the pronouncement of legal judgments, and the recitation of saga all represented in the extant literature. Indeed, Irish social structure was in many ways defined by such oratorical roles. However, these traditions must be understood within the context of the late antique and early medieval world.

In many ways, the intellectual history of medieval Ireland is the intellectual history of the Christian Latin West. However, Irish learning and literature is clearly distinct and reflects Irish social and cultural values as much as the influence of the Latin tradition. Contemporary scholars often refer to Irish learned and literary texts as “syncretic.” The tradition is vast, but some texts are better suited for a history of rhetoric class. I will organize this resource according to period, language, and genre. The Early Modern period is also quite important, as by the thirteenth century Irish scholars were intensely engaging with Roman epic and Virgilian commentaries, and by the fourteenth and fifteenth century, the Irish were working within the contemporary trends of Continental Europe and Britain, but always with a distinctly Irish “flavor.”

However, I think it important to first dispel some of the myths associated with early Ireland. Throughout the twentieth century, there was a strong tendency among scholars and in popular culture to paint a picture of early Ireland as one shrouded in “Celtic Mists.” Outside of the reaches of the Roman Empire, “Celtic” culture was preserved, and the surviving texts provide a window on the Iron Age. Indeed, these perspectives still persist today. However, as early as the third century CE, the Irish were involved in maritime trade with Roman Britons and the Mediterranean World, and the introduction of Christianity had a profound impact on Irish culture and society. With the exception of the inscriptions on standing stones known as ogam stones, all of the surviving texts we have from the early period are exactly that, texts. The ogam stones, along with the carved standing crosses, are excellent examples of material rhetoric, and these date to the pre-historic era, some perhaps as early as the third century CE, though the majority dating to the fifth century. Ogam is an alphabet that consists of a series of dashes across a line representing the Roman alphabet, and ogam stones likely marked burial sites and territorial boundaries. Importantly, this form of writing pre-dates the arrival of Christianity.

With the introduction of Christianity came the introduction of literacy, and it is likely that the extant manuscripts were produced within monastic scriptoria. Also, the early Irish did not see themselves as “Celts,” but rather as Gaels, and the identification of the Irish as Celts is a linguistic one. Such descriptions are fraught, and the student of early Ireland must tread carefully. Therefore, treating this literature as evidence of Celtic culture and mythology is controversial. This being said, the Latin and vernacular learning of early medieval Ireland is a rich resource for the student of rhetoric, and as more editions and translations of medieval texts become available, this tradition will change the dominant narratives of histories of medieval rhetoric.

Latinate Texts – 5th to 9th Centuries

The Latinate tradition in Ireland begins with St Patrick whose writings survive in several continental manuscripts, as well as a ninth-century Irish manuscript known as Liber Ardmachanus, or Book of Armagh. The surviving writings are the Epistola ad Milites Corotici (Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus) and Confessio (Confession). Scholarly consensus holds that, though these texts survive in much later manuscripts, they can be dated linguistically to the fifth century. Patrick was born to a noble Romano-British family in the fourth century. Though his dates and exact place of birth cannot be assigned with certainty, he tells us in his writings that his father was a decurion, another way of describing a curiales, a member of the ruling class that managed Roman provinces for the Empire. Patrick was wealthy, and his father and grandfather were also members of the clergy. He was captured and enslaved by the Irish at the age of about 16, but he escaped a few years later and returned home. Soon after, he likely studied in southern Gaul where he would eventually take clerical orders and return to Ireland as a bishop. His bishopric was not authorized by Rome, but likely by the Roman British Church. Patrick tells us he renounced his title to nobility, as well as his inheritance, in order to follow his Christian calling. In this, we see evidence for Patrick having been trained within the milieu of Paulinus of Nola or a similarly oriented monastic community in late fourth-century Gaul.

The Epistola is a letter of admonishment to a Romano-British king, Coroticus, for his raiding and slaughter of numerous recently converted Christians in Ireland, many of whom were sold into slavery among the “apostate Picts.” A rhetorical analysis of this letter has revealed that Patrick was trained in a form of Roman rhetoric, though within a monastic context. The letter’s organization, skilled deployment of numerous rhetorical figures, impactful appeals to pathos, and sophisticated chains of scriptural allusion (in place of the traditional Roman allusion to Classical sources), all bear the mark of a complex rhetorical performance. Though there are few allusions to texts other than the Latin Vulgate and Vetus Latina Bibles, the letter is clearly a product of rhetorical training. It is important to note, too, that letters were intended to be read aloud and performed in Late Antiquity. A letter was often sent with a skilled messenger, accompanied by an envoy, and the whole display would have been performed in front of a large audience. Patrick’s Epistola is of interest to historians of rhetoric not only for evidence of the continuation of rhetorical education in late fourth- or early fifth-century Britain, but also as a rhetorical artifact. Patrick’s letter provides us with an early example of rhetorical practice in Ireland, but it also sheds much light on sub-Roman Britain. A century later, the British writer Gildas will be of great interest.

Patrick’s Confessio is a written response to allegations made by “seniores” of the British Church who had called a synod to question the legitimacy of his bishopric in Ireland. The Confessio is reminiscent of Augustine’s Confession, and within this fascinating text we find much evidence for the nature of rhetorical learning in the Late Antique West. There are dreams and visions built on complex figuration, skillful deployment of rhetorical figures and, again, a hooking and chaining of scriptural allusions all set to the purpose of Patrick’s defense of his mission to Ireland. Finally, both of Patrick’s extant writings also point to a shift in stylistic values and the dominance of not only biblical learning, but also simplicitas (simplicity of style) and rusticitas (rusticity), both humility topoi that grew in importance in the fourth through the seventh centuries.

Though Patrick’s writings are the earliest, the Latinate tradition is extensive in early medieval Ireland. Perhaps most famous for his rhetorical abilities is the Irish peregrinus (“self-exiled monk”) Columbanus (543-615 CE), who has left a wealth of writings. Among these, we find five letters, numerous sermons, a monastic rule, and perhaps even poetry, though the authenticity of the poems is contested. Columbanus writes in a style referred to as “Hisperic.” Hisperic Latin was common throughout the Insular world in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, and several British and Irish writers exemplify this bombastic, highly ornamental, and archaizing tendency. Columbanus provides some of the earliest substantiated evidence for the nature of Irish monasticism and monastic learning in late sixth- and early seventh-century Ireland.

As a peregrinus, Columbanus left Ireland in the late sixth-century to spend the rest of his life in Merovingian Gaul, establishing important monasteries (especially Bobbio and Luxeuil) and getting involved in Church affairs. Peregrinatio among the Irish is worthy of rhetorical study in its own right. Columbanus’s biographer, Jonas, writes of him that he dedicated himself to litterarum doctrinis et grammaticorum studiss “the study of literature and grammar.” This dedication to study of the liberal arts reveals itself most fully in Columbanus’s letters. In Letter IV, Columbanus writes to Pope Boniface, admonishing him for his poor handling of the “Three Chapters Controversy,” an incredibly brave move that best captures his rhetorical zeal. This letter, as well as his letter to Pope Gregory the Great are prime examples of Christian rhetoric in Late Antiquity.

A text representative of a fusion of native and ecclesiastical learning is the Hisperica Famina (“Western Sayings”). This collection of verse written in Hisperic style includes description of the daily life of a student, common objects found in the monastery, as well as landscape descriptions. These descriptions, however, are set in the midst of a rhetorical battle between a group of monks and wandering scholars who debate who has the most rhetorical skill. Gabriell Knappe has argued that the Hisperica were likely influenced by Priscian’s Latin translation of Hermogenes’ progymnasmata, the Praeexercitamina. Stone has followed Knappe’s lead, placing the Hisperica within the context of Late Antique rhetorical practices and Irish learning.

There are a number of surviving hagiographies that demonstrate the influence of secular and ecclesiastical learning, including Virgil (especially Jonas’s Life of Columbanus). Hagiography draws on epideictic rhetoric and is a prime example of the versatility of the rhetorical arts in the late antique and early medieval periods.

Though there are a number of other important texts listed in the primary sources, the last texts to be discussed will be the grammatical. In the seventh century, interest in grammatical handbooks proliferated in Ireland. In order to contribute to Latin Christendom, the Irish, who were not native Latin speakers, had to learn the language. Donatus was too difficult, as his grammar was intended for native Latin speakers. Therefore, Irish scholars created their own grammatical handbooks, several of which survive today. In at least one instance, the Irish author of the grammar adapted Donatus for a beginning student and replaced all pagan allusions with Biblical examples, thus Christianizing Donatus. An important seventh-century vernacular grammar, the Auraicept na nÉces (“The Scholar’s Primer”), demonstrates early linguistic theorizing and serves as an important book for understanding the ogam alphabet. In these handbooks, there is active linguistic theorizing and sections of rhetorical figures.

Rhetoric and the Vernacular Tradition

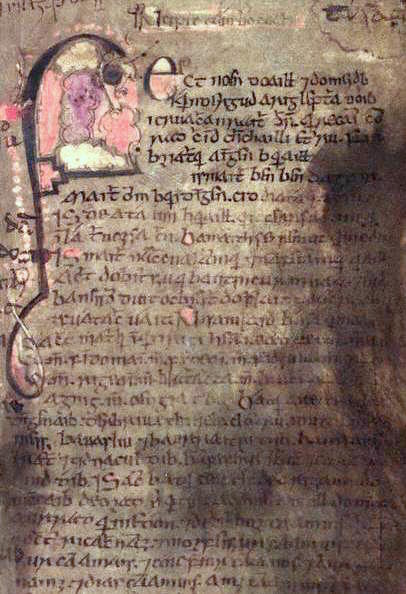

The vernacular of early Ireland is known to scholars today as Old Irish, Sengoídelc. It is an Indo-European language of the Goidelic Celtic family. For this reason, Irish culture is often identified as a Celtic culture; however, it is important to note that the early Irish were not aware of a shared linguistic cultural heritage among themselves and their “Celtic” neighbors. Vernacular Irish is divided into three distinct periods. The Old Irish period (or archaic Irish) is witnessed in texts composed between 600-900 CE. The Middle Irish period ranges from 900-1200 CE, and Early Modern Irish from 1200-1600 CE. Most evidence for the language and literature of the Old Irish period comes from later manuscripts, many dating between 1100-1500 CE, though the texts they contain have been dated linguistically and based on text-internal evidence to as early as the 630s. The ninth-century Book of Armagh is the oldest manuscript containing continuous Irish prose, but the late eleventh-century Lebor na hUidre (“Book of Dun Cow”) is the oldest manuscript containing complete secular material in prose and verse. By the ninth century, Irish began to replace Latin as the chosen medium in Irish monastic scriptoria.

Vernacular Law-Texts and Saga

Before the coming of Christianity, there was a learned caste in Ireland known as the Áes Dána (“people of arts”). By the seventh century, the native learned caste had come to be known as the filid (fili, sg., filid, pl.), and evidence from early law-texts shows they worked alongside clerical scholars in scriptoria, and in some cases one could be both a fili and a cleric. The filid, sometimes translated as ‘poet-jurist,’ but also containing the archaizing meaning ‘poet-seer,’ practiced filidecht, which covered the entire field of poetry, history, genealogy, biography, grammar, ancient lore, and the law. Poetry and law were closely associated, as the law-texts often represent judgments being rendered in a form of verse called roscad, a highly rhetorical and ornamented form of speech found in law-texts and saga. In addition to the fili, there was also the brithem, who was a judge who could not travel widely like the filid, but was required to stay with the king of a túath at all times.

Irish legal specialists composed the largest body of vernacular legal texts in all of medieval Europe. The filid gave judgments in a type of verse known as roscada (sg. roscad). The language of roscada is obscure, highly stylistic, performative, and rhetorical, and it often consists of maxims or aphorisms. Such passages are marked by a marginal ‘r’ in manuscripts which is often translated as ‘retoiric.’ While the nature and origin of such discourse is debated, Johan Corthals argues that though there may have been a native verse prior to the arrival of Latin learning, it developed in textual form from late antique rhetorical traditions. It is also a possibility that roscada were intentionally obscure (dorcha, ‘darkened’) and archaic, as this may have given it an air of authenticity, and it may have also served to protect the coveted knowledge of this elite, learned class.

Roscada are central to the law-texts, one of which quotes the Rhetorica ad Herennium in Latin. The pronouncement of judgment in legal contexts, as well as the narratives that often surround them, provide the student of rhetoric with insight into the syncretic nature of the learned legal tradition. Poetry was also important in the legal tradition, and the poem “The Cauldron of Poetry and Learning” has been noted for its fusion of native and Roman learning, drawing on the myth of a sacred well, the Well of Segais, from which all knowledge flows forth, and on which a student must call when reciting poetry or judgments.

Of all vernacular literature produced in medieval Ireland, the “sagas” have received the most scholarly attention. This vast tradition is often divided into four cycles: The Mythological Cycle, The Ulster Cycle, The Finnian Cycle, and the Cycle of the Kings (or “Historical Cycle”). For a student of rhetoric, the speeches within the saga texts are perhaps of greatest interest.

By the tenth and eleventh centuries, Irish scholars had begun “translating” Roman epic. These translations, however, are loose, and represent the practice of imitatio and aemulatio. In the midst of this scribal activity, we also see an increase in the production of saga texts, and Roman epic had a profound influence on the shape the sagas took. Though treated for years as evidence of Irish mythology and as materials only worthy of the fringes of medieval literature, scholars believe that Irish scribes saw both Roman epic and the sagas they produced as historiography, or “pseudo-historiography.” In late antique and early medieval historiography, direct speech was a central concern, and progymnasmatic exercises such as ethopoeia and prosopopeia were central to the composition of history. Though the Roman texts were drawn on in a number of ways, the Irish sagas clearly represent Irish tales that have come down through oral tradition. Therefore, the speeches in these sagas offer an excellent source for understanding the interaction of native and classical oratorical traditions. The Táin Bó Cúailnge (Cattle Raid of Cooley) and Togail Troí (Destruction of Troy) are prime examples, the former being the most extensive and popular native saga, the latter being the first vernacular translation of Dares Phrygius’s Destruction of Troy in the Middle Ages. Since Dares’s Latin text is stylistically bare bones, there is much to be said of the speeches in the Irish translation.

Visual Rhetoric in Early Ireland

In addition to this wealth of vernacular texts, the Irish are famous for manuscript illuminations, the most famous examples including Book of Kells, Lindisfarne Gospels, Book of Durrow, and Book of Armagh, to name only the most famous. These manuscripts are visually stunning and a fantastic example of the visual rhetoric of manuscript illumination. There are also a number of surviving ogam stones and inscribed crosses that demonstrate the importance of material rhetoric in the medieval Irish landscape.

Primary Sources

- Ahlqvist, Anders. The Early Irish Linguist: An Edition of the Canonical Part of the Auraicept na n-Éces. Helsinki: Societas Scientiarum Fennica, 1982.

- Bauer, Bernhard, Rijcklof Hofman, and Pádraic Mauer. St Gall Priscian Glosses. http://www.stgallpriscian.ie/.

- Best, Richard Irvine, and M.A. O Brien [eds.]. Togail Troí, from the Book of Leinster, vol. IV. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1966

- Bieler, Ludwig. Libri Epistolarum Sancti Patricii Episcopi: Introduction and Commentary. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy Dictionary of Medieval Latin from Celtic Sources, 1993.

- —. The Patrician Texts in the Book of Armagh. Dublin: The Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1979.

- Binchy, D.A. ‘The Pseudo-historical Prologue to the Senchus Már.’ Studia Celtica 10-11 (1975-1976): 15-28.

- Bischoff, Bernhard and Bengt Lofstedt eds. Anonymus Ad Cuimnanum. Brepols: Typographi Brepols Editores Pontifichi, 1992.

- Breatnach, Liam. Uraicecht Na Ríar: The Poetic Grades in Early Irish Law. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1987.

- —. “The Cauldron of Poesy.” Eriu (1981): 41-73.

- Corthals, Johan. “Stimme, Atem und Dichtung: Aus einem Lehrbuch für die Dichterschüler (Uraicept na Mac Sésa).” Helmut Birkhan Ed. Kelten-Einfälle an der Donau. Akten des Vierten Symposiums deutschsprachiger Keltologinnen und Keltologen…Linz/Donau 17.21 (2007): 127-48.

- Calder, George. Auraicept na n-éces: The Scholars’ Primer. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1995.

- —. Togail na Tebe: The Thebaid of Statius. Cambridge, 1922.

- Herren, Michael. Hisperica famina. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1974.

- —. The Hisperica Famina II: Related Poems. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1987.

- Hofman, Rijcklof. The Sankt Gall Priscian Commentaries Vol. 1 and 2. Munster: Nodus Publishing, 1996.

- Howlett, D.R. Liber Epistolarum Sancti Patricii Episcopi. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1994.

- “Illuminated Manuscripts.” Encyclopedia or Irish and Celtic Art. http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/cultural-history-of-ireland/illuminated-manuscripts.htm#context.

- Irish Inscribed Stones Project. Foundations of Irish Culture Project, National University of Ireland, Galway. http://www.nuigalway.ie/irish-inscribed-stones-project/

- Irish Script on Screen. Royal Irish Academy. https://www.isos.dias.ie/.

- Koch, John T. and John Carey Eds. The Celtic Heroic Age: Literary Sources for Ancient Celtic Europe and Early Ireland and Wales. Celtic Studies Publications, 2003.

- Lofstedt, Bengt ed. Ars Ambrosiana: Commentum Anonymum In Donati Partes Maiores. Brepols: Turnhous, 1982.

- —. Der Hibernolateinische Grammatiker Malsachanus. Uppsala: Studia Latina Upsaliensia, 1965.

- Ó hAodha, D. ‘The Irish Version of Statius’ “Achilleid”’. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature 79 (1979): 83-138.

- O Hara, Alexander and Ian Wood Trs. Jonas of Bobbio: Life of Columbanus, Life of John of Réomé, and Life of Vedast.Translated Texts for Historians LUP, 2017.

- O’Rahilly, Cecile [ed. and tr.], Táin bó Cúalnge: from the Book of Leinster, Irish Texts Society 49, Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1967.

- Poppe, Erich, A new introduction to Imtheachta Æniasa: The Irish Æneid: the classical epic from an Irish perspective, Irish Texts Society, Subsidiary Series 3, London: Irish Texts Society, 1995.

- Peters, Eric. ‘Die irische Alexandersage’, ZCP 30 (1967): 71-264.

- Sharpe, Richard Ed and Tr. Life of St Columba. Penguin Classics, 1995.

- Stokes, Whitley [ed. and tr.], Stokes, Whitley. Togail Troí: The Destruction of Troy. Calcutta, 1881.

- —. “In cath catharda: The civil war of the Romans. An Irish version of Lucan’s Pharsalia”, in: Windisch, Ernst, and Whitley Stokes (eds.), Irische Texte mit Wörterbuch, 4 vols, vol. 4:2, Leipzig, 1909. v–viii, 1–581.

- Walker, J.S.M. ed. Sancti Columbani Opera. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1970.

- Walsh, Maura and Dáibhí Ó Cróinín. Cummian’s Letter De Controversia Paschali: Together with a Related Irish Computistical Tract De Ratione Conputandi. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 1988.

Secondary Sources

- Binchy, D.A. “Bretha Nemed.” Ériu 17 (1955): 4-6.

- Boyle, Elizabeth. “Allegory, the áes dána and the liberal arts in Medieval irish literature.” Hayden, Deborah and Paul Russell eds. Grammatica, Grammadach and Gramadeg: Vernacular Grammar and Grammarians in Medieval Ireland and Wales. Amsterdam Studies in the Theory and History of Linguistic Science – Series 3: (2016): 11-34.

- Bracken, Damien. Alexander O Hara, ed. “Columbanus and the Language of Concord.” Columbanus and the Peoples of Post-Roman Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Breatnach, Liam. “Satire, Praise, and the Early Irish Poet.” Ériu 56 (2006): 63-84.

- —. A Companion to the Corpus iuris Hibernici. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 2005.

- —. “On Satire and the Poet’s Circuit.” Eds. Cathal G. Ó hÁinle and Donald E. Meek. Unity in Diversity: Studies in Irish and Scottish Gaelic Language, Literature and History. Dublin: School of Irish, Trinity College (2004): 25-35.

- —. ‘Poets and Poetry.’ Progress in Medieval Irish Studies. Maynooth: An Sagart (1996): 65-77.

- —. ‘Canon Law and Secular Law in Early Ireland: the Significance of Bretha Nemed.’ Peritia 3 (1984): 439 – 459.

- Carey, John. “The Three Things Required of a Poet.” Ériu XLVIII (1997): 41 – 58.

- —. “Obscure Styles in Medieval Ireland.” Mediaevalia 19 (1996): 23-39.

- Chapman-Stacey, Robin. Dark Speech: The Performance of Law in Early Ireland. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

- Charles-Edwards, T.M. The Medieval Gaelic Lawyer. Quiggin Pamphlets on the Sources of Mediaeval Gaelic History 3. Cambridge, 1999.

- —. Early Christian Ireland Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- —. “Early Irish Law.” Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, Ed. A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. 331-370.

- Clarke, Michael. “International Influences on the Later Medieval Development of Togail Troi.” Early Medieval Ireland and Europe: Chronology, Contacts, Scholarship. A Festschrift for Dáibhí Ó Cróinín. Munster, Nodus, 2016.

- —. “Demonology, Allegory and Translation: The Furies and the Morrígan.” Ed. Ralph O Connor. Classical Literature and Learning in Medieval Irish Narrative. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2014.

- —.’Linguistic Education and Literary Creativity in Medieval Ireland.’ Cahiers de l’ILSL, N 38 (2013): 39-71.

- Cornel, Dora and Franziska Schnoor. The Cradle of European Culture: Early Medieval Irish Book Art. Schwabe Verlasgsgruppe, 2018.

- Corthals, Johan. “Decoding the Caldron of Poesy.” Peritia 24-25 (2013): 74-89.

- —. ‘The Áiliu Poems in Bretha Nemed Dédenach.’ Éigse 37 (2010): 59-91.

- —.“Early Irish Retoirics and their Late Antique Background.” Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies 31 (1996): 18-37.

- Davies, Oliver. Celtic Spirituality. Paulist Publishing, 2000.

- Dumville, David. St Patrick 493-1993. Studies in Celtic History 13, 1999.

- Hayden, Deborah. ‘Some Notes on the Transmission of Auraicept na nÉces.’ Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 32 (2014): 134-179.

- —. ‘Poetic Law and the Medieval Irish Linguist: Contextualising the Vices and Virtues of Verse Composition in Auraicept na nÉces.’ Ériu 64 (2011): 1-21.

- Hayden, Deborah and Paul Russell eds. Grammatica, Grammadach and Gramadeg: Vernacular Grammar and Grammarians in Medieval ireland and Wales. Amsterdam Studies in the Theory and History of Linguistic Science – Series 3: 2016.

- —. ‘Poetic Law and the Medieval Irish Linguist: Contextualising the Vices and Virtues of Verse Composition in Auraicept na nÉces.’ Ériu 64 (2011): 1-21.

- Herren, Michael W. ‘Scholarly Contacts Between the Irish and the Southern English in the Seventh Century.’ Peritia 12 (1998): 24 – 53.

- —.Latin Letters in Early Christian Ireland. Brookfield: Ashgate, 1996.

- —. “Classical and Secular Learning among the Irish before the Carolingian Renaissance.” Florilegium 3 (1981): 118-157.

- Hillers, Barbara. In fer fíamach fírglic: Ulysses in Medieval Irish Literature. Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 16/17 (1996/1999): 15-38.

- Hofman, Rijcklof. ‘Some New Facts Concerning the Knowledge of Vergil in Early Medieval Ireland’. Études celtiques25 (1988): 189-212.

- —. Donat Et La Tradition De L’Enseignement Grammatical. Paris: Centre National De La Recherche Scientifique, 1981.

- —.’The Irish Tradition of Priscian.’ Manuscsripts and Tradition of Grammatical Texts from Antiquity to the Renaissance: Proceedings of a Conference held at Eirce, 16-23 October 1997, at the 11th Course of International School for the Study of Written Records. Mario De Nonno et al eds. Cassino: Edizioni Dell Universita Degli Studi Di Cassino, 257-287.

- Holtz, Louis. ‘Irish Grammarians and the Continent in the 7th Century.’ Columbanus and Merovingian Monasticism. H.B. Clarke and Mary Brennan eds. Oxford: BAR International Series 113, 1981.

- Howlett, David. ‘The Earliest Irish Writers at Home and Abroad.’ Peritia 8 (1994): 1 – 17.

- Johnson-Sheehan, Richard and Paul Lynch. ‘Rhetoric of Myth, Magic, and Conversion: A Prolegomena to Ancient Irish Rhetoric.’ Rhetoric Review 26.3 (2007): 233-252.

- Johnston, Elva. Literacy and Identity in Early Medieval Ireland. Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2013.

- Kelly, Fergus. A Guide to Early Irish Law. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 2005.

- —. Early Irish Farming: A Study Based Mainly on the Law-Texts of the 7th and 8th Centures AD. Early Irish Law Series. School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 2000.

- Kenney, James F., ed., Sources for the Early History of Ireland: Ecclesiastical. New York, 1966.

- Knappe, Gabrielle. ‘On Rhetoric and Grammar in the Hisperica famina.’ Journal of Medieval Latin 4.4 (1994): 130-162.

- Law, Vivien. The Insular Latin Grammarians. Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 1982.

- McLaughlin, Roisin. Early Irish Satire. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 2008.

- McManus, Damian. A Guide to Ogam. Maynooth: An Sagart, 1997.

- Melia, Daniel F. ‘The Rhetoric of Patrick’s Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus.’ Proceeding of the Annual CSANA Meeting 2008: CSANA Yearbook 10 (2008): 96 – 104.

- Miles, Brent. Heroic Saga and Classical Epic in Medieval Ireland. D.S. Brewer, 2011.

- —. ‘The Literary Set Piece and the Imitatio of Latin Epic in the Cattle Raid of Cúailnge’.

- Ulidia 2: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Ulster Cycle of Tales. Maigh Nuad: An Sagart: 2009.

- —. ‘Riss In Mundtuirc: The Tale of Harmonia’s Necklace and the Study of the Theban Cycle in Medieval Ireland. Ériu 57 (2007): 67-113.

- Ní Mhaonaigh, Máire. ‘The Peripheral Centre: Writing History on the Western “Fringe”’. Interfaces 4 (2017): 59-84.

- —.‘The Hectors of Ireland and the Western World’. John Carey et al Eds. Sacred Histories: A Festschrift for Máire Herbert (2015): 258-68.

- Ó Cathasaigh, Tomás. “The Literature of Medieval Ireland to c. 800: St. Patrick to the Vikings.” The Cambridge History of Irish Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- O Connor, Ralph. Classical Literature and Learning in Medieval Irish Narrative. Boydell & Brewer, Studies in Celtic History, 2014.

- —. The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel: Kingship and Narrative Artistry in a Mediaeval Irish Saga. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- O Hara, Frank. Columbanus and the Peoples of Post-Roman Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- O Cróinín, Dáibhí. Early Medieval Ireland: 400 – 1200. New York: Longman, 1995.

- —. ‘The Irish as Mediators of Antique Culture on the Continent.’ Science in Western and Eastern Civilization in Carolingian Times. Ed. Paul Leo Butzzer and Dietrich Lohrmann. Berlin: Birkhauser Verlag, 1993.

- Orchard, Andy. ‘The Hisperica Famina as literature’. Journal of Medieval Latin 10 (2000): 1-45.

- Poppe, Erich. “Caide máthair bréithre ‘what is the mother of a word’” Deborah Hayden and Paul Russell eds. Grammatica, Grammadach and Gramadeg: Vernacular Grammar and Grammarians in Medieval Ireland and Wales.Amsterdam Studies in the Theory and History of Linguistic Science – Series 3: (2016): 65-84.

- Poppe, Erich and Dagmar Schlüter. ‘Greece, Ireland, Ulster, and Troy: of hybrid origins and heroes’. Wendy Marie Hoofnagle and Wolfram R. Keller Eds. Other Nations: The Hybridization of Insular Mythology and Identity (2011): 127-44.

- Russell, Paul. An Introduction to the Celtic Languages. Boston: Routledge, 1995.

- Sharpe, Richard. ‘Books from Ireland, Fifth to Ninth Centuries.’ Peritia 21 (2010): 1-55.

- Stone, Brian James. The Rhetorical Arts in Late Antique and Early Medieval Ireland. Nieuwe Prinsengracht: Amsterdam University Press, forthcoming.

- —. “Scriptural Ethos and Imitation: The Pauline Epistles and St. Patrick’s ‘Confessio.’ Proceedings of the Celtic Colloquium 34 (2014): 240-268.

- Tranter, Stephen N. Hildegard L.C. Tristram eds. Early Irish Literature – Media and Communication. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag Tübingen, 1989.

- Wiley, Dan M. Ed. Essays on the Early Irish King Tales. Portland: Four Courts Press, 2008.

- —. ‘The Maledictory Psalms.’ Peritia 15 (2001): 261-278.Williams, Mark. Ireland’s Immortals: A History of the Gods of Irish Myth. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

About the Author: Brian J. Stone is the Director of Writing Programs and an Assistant Professor of English at Indiana State University. He has a PhD in English, Rhetoric and Composition from Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. His monograph, The Rhetorical Arts in Late Antique and Early Medieval Ireland, is forthcoming from Amsterdam University Press.